Matilda, Duchess of Saxony and Bavaria

My painting of Heinrich and Matilda, copied from a page of Heinrich's illuminated gospel

Matilda, Duchess of Saxony and Bavaria

Heinrich der Löwe, or Henry the Lion, seen

kneeling on the left of the picture in some rather snazzy red tights, is the

man who put Braunschweig on the map in the 12th century, and arguably

he remains the city’s most famous and celebrated son. At the height of his

power, he was one of the richest and most important princes in Europe: not

content with inheriting two major dukedoms (Saxony and Bavaria), he then

proceeded to obsessively enlarge these territories by whatever means possible

(everything from buying and bartering, to kidnapping the Archbishop of Bremen

and not releasing him until he agreed to hand over a chunk of his land). And

Braunschweig was his power base, giving the city a major boost both

economically and culturally: Heinrich promoted trade, substantially expanded

the city, built the cathedral that still stands today, and presided over a

brilliant court. But eventually his power-hungry ways got him into trouble, and

he was outlawed, stripped of his lands and forced into exile. Despite this less

than glorious end to his reign, his legacy is still going strong in 21st

century Braunschweig, thanks to the city’s strong identification with his

epithet: the name “Löwe” is liberally deployed by the city’s marketing board

and assorted business, sports teams and the like.

A drawing I did of the Burgplatz in Braunschweig, with Heinrich's lion statue on the right

But enough about Heinrich, because it is not him

who I have chosen to make the subject of my first blog post, but rather his

wife Matilda. Matilda intrigues me not only because she was a woman, and I find

it hard to resist a feminist-revisionist take on history, but also because she

was English, which leads me to feel a certain affinity with her, despite the

gap of over 800 years which separates our respective stays in the city (and

despite the fact she was a medieval princess, which I definitely am not,

although I would be more than willing to dress up as one). She is standing on the right of the picture, which is copied from Heinrich’s gospel book, one of those gorgeously

illustrated medieval tomes that became the world’s most expensive book in 1983

(it was bought for approx. £12 million...probably not at Oxfam Books). Matilda

was the daughter of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine, and the older sister of

the future Richard the Lionheart and “bad” King John. Eleanor is a fascinating

figure who led a rather racy life: married to two different kings, divorced

from one of them, imprisoned by the other, Henry, for 16 years, and eventually

ruling England as regent after his death, as well as being a great patron of

troubadours, the doyenne of courtly love. In comparison to her illustrious and

long-lived mother, there is a lot less information available on Matilda’s life,

but there are a few facts that give an insight into the person she must have

been. She was all of 12 years old when, in 1168, she married Heinrich and came

to Braunschweig. (Her husband was around 25 years her senior – decidedly dodgy,

I know, but royal daughters were of course pawns in their parents’ power plays,

strategically married off to achieve the most advantageous alliances). Her

first impressions may well have been dispiriting – after the lively, cultivated

milieu of her parents’ court, where she had been surrounded by troubadours and

other artists, her new home in Saxony probably seemed like a dull, provincial place

where there was more focus on practical matters than poetry. Years of

turbulence and uncertainty lay ahead of her, due to her husband’s constant

involvement in military campaigns and controversies, and his eventual downfall,

as mentioned above. But she must have been a positive and determined sort,

because she didn’t simply resign herself to her lot. As well as dutifully performing

her role as duchess and wife, bearing five children, she also set about

bringing some culture and prestige to Braunschweig, turning Heinrich’s court

into a more glamorous, civilised affair than it had been upon her arrival. For

example, she helped to introduce the French poetry she was familiar with from

her youth – she is thought to have initiated the translation into German of one

of the most important epic poems of the medieval period, the Song of Roland. Together

with Heinrich, she also donated the famous Mary altar to the Braunschweig

cathedral: a simple slab of stone supported by five bronze pillars, it has

survived the centuries and still looks as robust as ever.

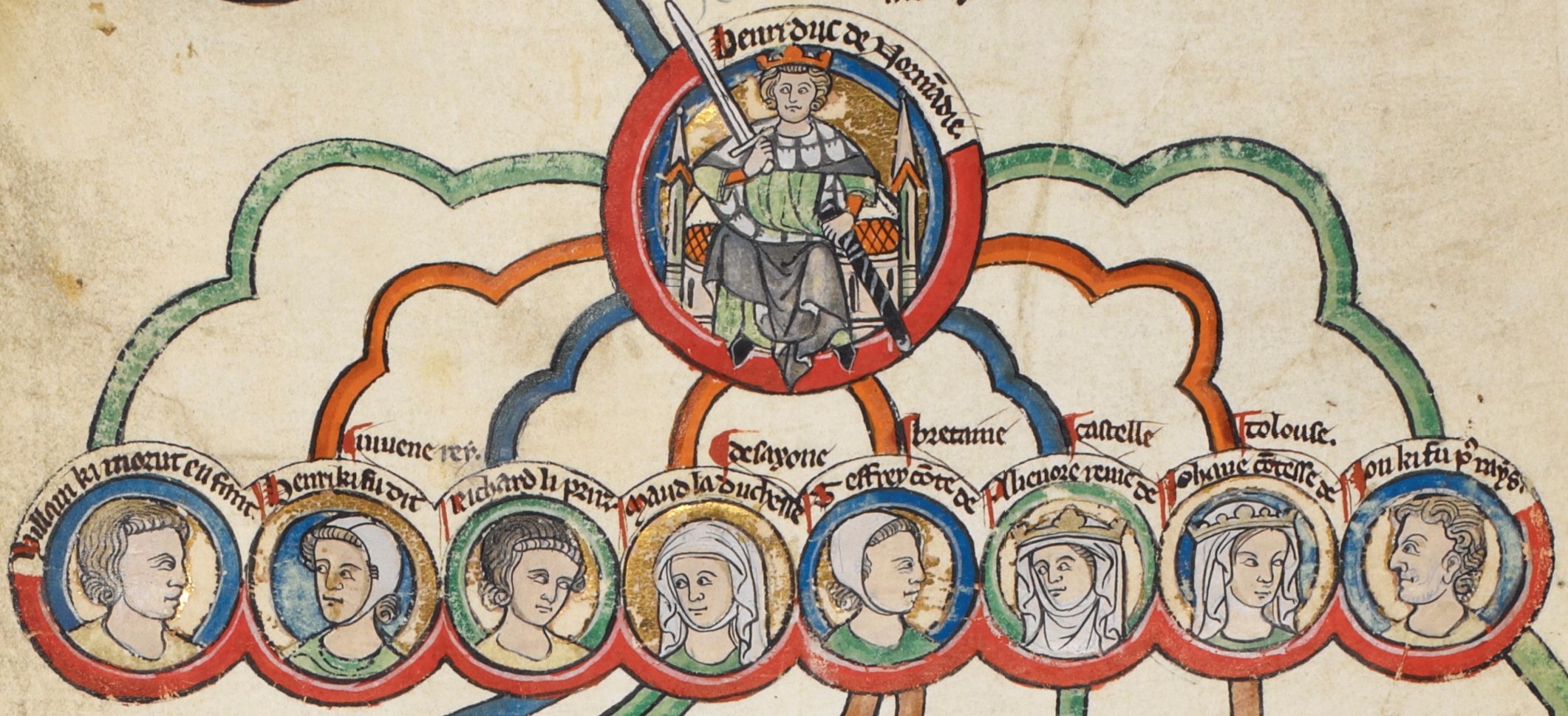

King Henry II and his children, including Richard the Lionheart (third from left), Matilda (fourth from left) and John (far right)

But her activities weren’t confined to the sphere

of art and culture. The chronicler Arnold von Lübeck recorded that she was always

kind and generous to the poor and needy. And when her husband went off on a

jaunt to the Holy Land, he left her in charge, which suggests to me that he

must have respected her judgement and strength of character, even if her leadership

role was mostly symbolic. Another story relates how she was left alone in the

town of Lüneburg after Heinrich rode off to battle in another town, only for

the Emperor and his army to show up intending to take the city by force. Matilda

kept her composure and let it be known to the Emperor that Lüneburg was part of

her dowry. He respected this and moved his troops on, leaving the city intact.

Heinrich’s downfall and subsequent exile did have

a happy outcome for Matilda: Heinrich was given refuge at the court of his father-in-law

Henry, which meant that she was able to return to her homeland. The family went

first to Normandy (under English rule at that time), where the troubadour

Bertran de Born wrote two love poems in Matilda’s honour, suggesting she may

have possessed something of her mother’s famed beauty and charm. Then, in 1184,

Matilda returned to England itself. I’d like to think it was a happy homecoming

for her. She stayed for a year, during which time she gave birth to a son, William,

and spent Christmas 1184 with her husband and her father at Windsor – a lovely

little fact, at least to my probably too fanciful imagination, which pictures

the three of them sitting cosily round a roaring log fire, toasting each other’s

health with goblets of mead.

She accompanied Heinrich back to Braunschweig a

year later, and died there in 1189 aged only 33. Her effigy still has pride of

place next to her husband’s in the central aisle of Braunschweig cathedral.

Effigies of Heinrich and Matilda

Sources:

Wikipedia

Braunschweig:

Kleine Stadtgeschichte, Dieter Diestelmann

Braunschweiger

Frauen, Gestern und Heute: Sechs Spaziergänge,

Sabine

Ahrens et al.

Heinrich

der Loewe, Paul Barz

Just excellent reading Charlotte, and I love the picture! You have your Mother's gift.

ReplyDeleteFascinating! It's incredible to think that Matilda did so much with such a short life. Dying at the age of 33 and leaving 5 children! Your drawing of the Burgplatz is so impressive - what a complicated subject.

ReplyDelete